N’Djamena – Around 5.4 million children in Chad were recently vaccinated against polio in a broad and synchronised campaign. Carried out with support from World Health Organization (WHO) and Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) partners, the immunisation drive included neighbouring Cameroon, Niger and the Central African Republic.

In Chad, where polio was detected in 2019 after no cases were reported for six years, efforts were made to ensure communities living in hard-to-reach locations, such as nomadic populations, were not left behind.

Nomadic populations account for 3.4% of Chad’s population. They are among the most underserved communities, with very limited access to health services.The first polio campaign targeting nomadic children, who at the time comprised 40% of the country’s total polio cases, was launched in 2012. Thanks to effective micro-planning and geolocation tools, in 2023 polio vaccination teams reached 51 242 nomadic children nationwide.

WHO and partners opted for a decentralized approach to micro-planning, which is an essential component of the polio campaign toolbox. This requires health centres to take responsibility for counting the number of nomads in their zone, and compiling comprehensive data to ensure every child receives their polio vaccine, regardless of the difficulty in reaching them.

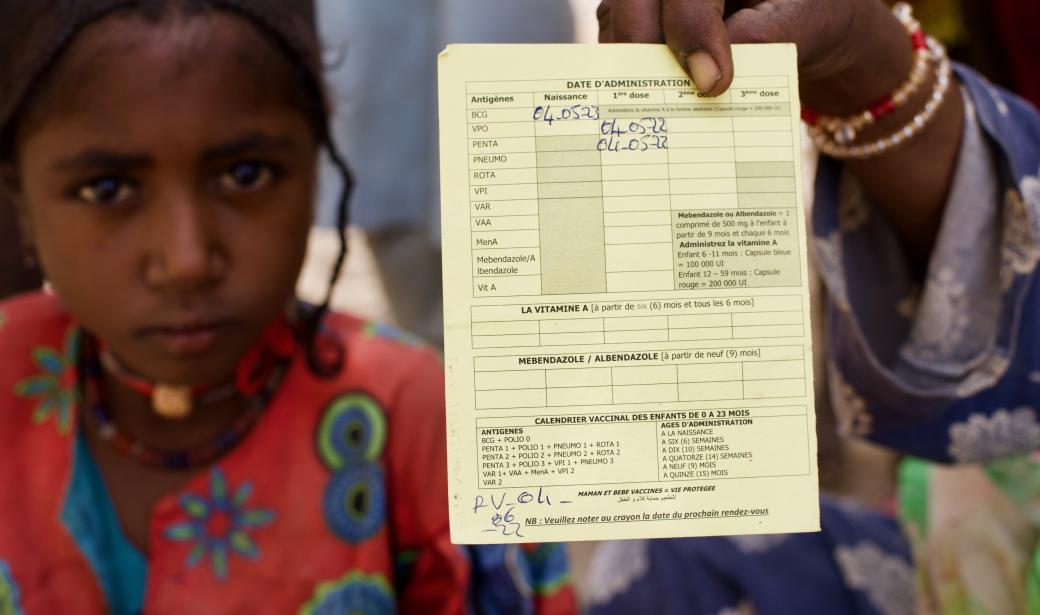

As the campaign draws to a close, Kouta is supervising the work of his teams, verifying finger and house markings, as well as vaccination documents.

“Unfortunately, we’ve had some difficulties with nomadic communities accessing health services,” he adds. “There were a few instances when they were not included in mosquito nets or vitamin distribution.”

To rebuild their lost trust, leaders are being engaged and tailored communication approaches adopted. Among these are vaccination micro-plans.

“The hardest is actually getting health centres to understand that nomads must be included in their target,” he stresses.

“Thanks to this form, we can design a micro-plan to reach nomadic children, which includes the number of settlements, geographic coordinates and exact target numbers for the vaccination,” Ahmed explains.

“We’ve worked closely with nomadic leaders and recruited specialized teams. We’ve had excellent results so far. The Ministry of Health even created a programme dedicated to nomadic populations,” explains Camara.

“I've vaccinated 20 nomadic children over the past two days,” says Allaramadji, who is busy speaking to families and checking for any missed children during mop-up operations.

“We don’t usually mark tents because they’re made of material that is difficult to write on. If we use a marker, people can’t erase that and we need to respect their homes. So we mark the nearest tree instead,” he explains.

"I do what I can to support the children. Whether I am a nomad or not, we are all part of the same community.”

Chargée de Communication

OMS Tchad

Email : coumbalay [at] gmail.com (coumbalay[at]gmail[dot]com)